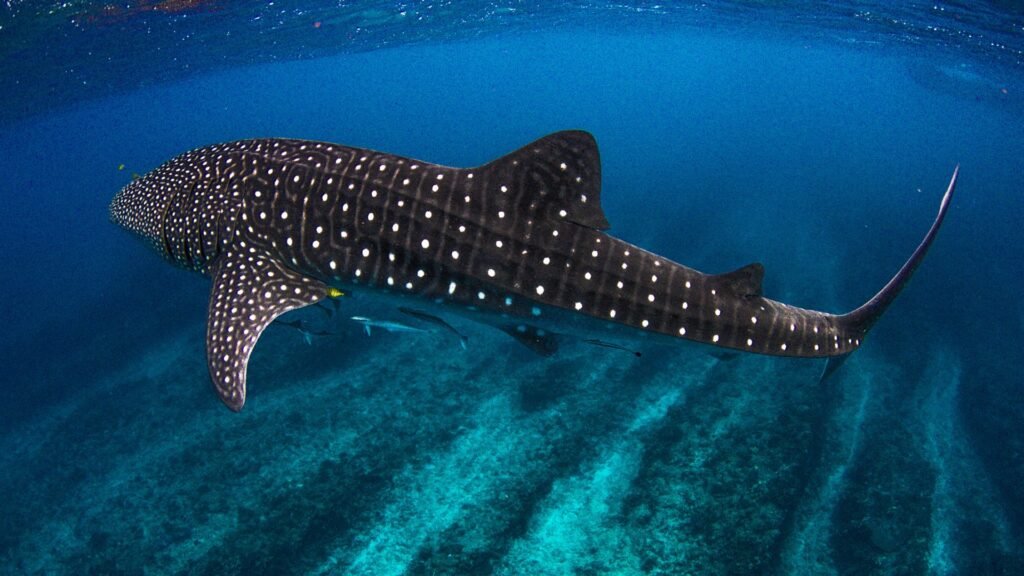

A recent scientific investigation into a major whale shark aggregation site has revealed an alarming and near-universal prevalence of anthropogenic scarring on the resident population. The findings indicate that the very industry built around observing these animals—ecotourism—is the primary driver of sub-lethal, physical injury. This study presents a critical paradox where a conservation-funded enterprise is inflicting direct, measurable harm on the species it purports to protect, raising urgent questions about the sustainability and ethical framework of current operational models.

The whale shark (Rhincodon typus), the world’s largest fish, is a globally sought-after species for marine ecotourism. Its docile nature and predictable aggregation patterns in specific coastal locations have fueled a multi-million dollar industry. However, mounting evidence suggests that intense, unmanaged tourism activities are exerting significant negative pressure on these animals. This article synthesizes the findings of recent photo-identification surveys that document the extent and nature of scarring on whale sharks in a high-traffic tourism destination.

Evidence and Causality

The core finding of the research is the exceptionally high incidence of scarring, with nearly every individual shark cataloged bearing marks of human origin. These injuries are systematically categorized into distinct types:

- Major Lacerations and Propeller Strikes: Deep, linear or curvilinear cuts, often in parallel sets, are consistent with impacts from boat propellers. These are among the most severe injuries, capable of cutting through the shark’s thick dermal layer and causing significant blood loss and potential for secondary infection.

- Abrasions and Hull Scrapes: Large patches of abraded skin, typically on the dorsal surface and fin leading edges, correlate with contact from the hulls of vessels. These injuries, while less acute than propeller strikes, can remove protective mucus layers and skin, increasing vulnerability to pathogens.

- Amputations and Disfigurement: In some cases, partial amputation of the dorsal or caudal fins has been recorded, severely impacting the animal’s hydrodynamic efficiency and long-term survival prospects.

The primary causal agent identified is the high volume of unregulated tour boats. The slow, surface-feeding behavior of whale sharks makes them exceptionally vulnerable. In a competitive tourism environment, vessel operators often engage in high-risk maneuvering to provide clients with the closest possible encounters, leading to a high probability of direct strikes. The spatial and temporal overlap between peak shark feeding times and peak tourism hours creates a perfect storm for these negative interactions.

Biological and Conservation Implications

The physiological consequences of these sub-lethal injuries are a significant concern. Open wounds require substantial energy to heal, diverting resources from other vital functions like growth and reproduction. Furthermore, they serve as entry points for bacterial and parasitic infections. Chronic stress from constant vessel noise and physical contact can lead to altered feeding behaviors and site avoidance, potentially disrupting the ecological dynamics of the aggregation site.

From a conservation standpoint, this phenomenon challenges the very definition of “sustainable ecotourism.” The industry’s viability is dependent on a healthy, thriving population of whale sharks, yet its current practices are contributing to the physical degradation of the asset itself. This creates a negative feedback loop where the damage could eventually lead to a decline in the shark population or their departure from the area, ultimately causing the collapse of the local tourism economy.

Recommendations for Mitigation

The evidence strongly supports the immediate implementation of a robust regulatory framework to mitigate vessel-related impacts. Key management strategies should include:

- Mandatory Standoff Distances: Legally enforcing a minimum approach distance for all vessels.

- Vessel Quotas: Limiting the number of boats permitted within the interaction zone at any given time.

- Propeller Guards: Mandating the use of propeller guards on all tour boat engines to reduce the severity of injuries in case of accidental contact.

- Certified Training: Requiring all tour operators and guides to undergo mandatory training and certification in responsible wildlife interaction protocols.

The scars borne by the whale sharks serve as a visible, undeniable ledger of human impact. They are a powerful indicator that the current model of ecotourism in this and potentially other locations is fundamentally unsustainable. Without a paradigm shift from a high-volume, high-impact approach to a low-volume, regulated, and welfare-centric model, we risk loving these gentle giants to death. The scientific data is clear: immediate and decisive management intervention is required to ensure that ecotourism can genuinely contribute to the conservation of Rhincodon typus, rather than to its steady decline.