Over the past two years, exceptionally warm ocean conditions have persisted across multiple basins, reshaping marine habitats and the services they provide. For Costa Rica, this means more frequent and longer marine heatwaves that stress coral reefs, alter the timing and distribution of key species, and influence activities such as diving, fisheries, and coastal tourism. Warmer surface waters also change how the ocean mixes and stores heat, with knock-on effects for weather, sea level, and coastal ecosystems.

This article explains what is driving recent ocean warming, how global patterns connect to Costa Rica’s Pacific and Caribbean coasts, and what these changes mean for emblematic species and livelihoods. You will find a clear overview of the 2024–2025 context, the mechanisms behind marine heat, local timelines of thermal stress, and practical actions for monitoring and adaptation. The goal is to translate robust science into actionable insight for nature lovers, guides, educators, responsible travelers, and decision-makers in Costa Rica.

The 2024–2025 Ocean Heat Surge

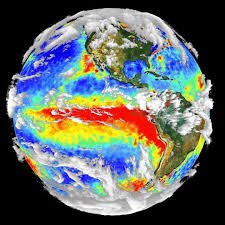

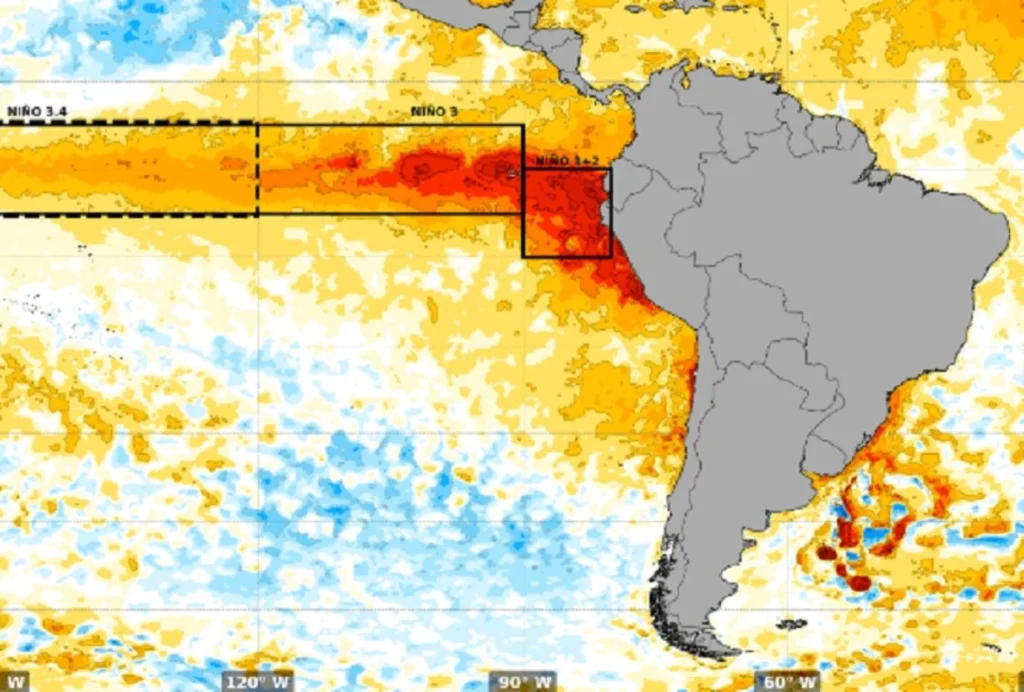

Between early 2023 and late 2024, global ocean temperatures reached unprecedented levels. Satellite and in-situ measurements showed that sea surface temperatures (SST) remained above historical records for months, with some regions exceeding the 90th percentile of their climatology for extended periods. This warming was not isolated—it spanned the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans, with particularly intense anomalies in the North Atlantic, the Caribbean, and the tropical Pacific.

In 2024, the global ocean heat content (OHC)—a measure of thermal energy stored from the surface to 2000 meters depth—also hit new highs. According to the annual analysis by Cheng et al. in Advances in Atmospheric Sciences, the ocean absorbed more than 90% of the excess energy trapped by greenhouse gases, making it the planet’s primary heat reservoir.

Marine heatwaves (MHWs), defined as prolonged periods of unusually warm ocean temperatures, became more frequent, longer-lasting, and more intense. NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch and Copernicus Climate Service reported widespread MHWs in the Caribbean and Eastern Tropical Pacific, with many events classified as “strong” or “severe.” These conditions triggered coral bleaching, disrupted fish migration, and altered the timing of biological events such as spawning and nesting.

Looking ahead to 2025, the transition from El Niño to neutral or La Niña conditions may cool parts of the Pacific, but the accumulated heat in the ocean remains high. This means regional MHWs could persist, especially in semi-enclosed basins like the Caribbean or along coastlines with limited upwelling. The ocean’s thermal inertia ensures that even short-term cooling phases do not erase the long-term warming trend.

In Costa Rica, both the Pacific and Caribbean coasts are exposed to these changes. The Pacific, influenced by ENSO dynamics, saw elevated SSTs near the Nicoya Peninsula and Gulf of Papagayo. The Caribbean, particularly the southern coast near Cahuita and Gandoca-Manzanillo, experienced prolonged heat stress that affected coral health and visibility for divers.

Section 3: Why It Happened — Key Drivers of Ocean Heat

The extreme ocean temperatures observed in 2024–2025 are not random fluctuations. They result from a combination of long-term human-induced warming and short-term climate variability, amplified by changes in ocean-atmosphere interactions. Understanding these drivers helps explain why marine heatwaves are becoming more frequent and intense—and why they’re likely to persist.

1. Anthropogenic Forcing

The primary driver of ocean warming is the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), and other gases trap heat, and the ocean absorbs over 90% of this excess energy. This long-term trend raises both surface temperatures and deep ocean heat content, creating a warmer baseline from which extreme events emerge.

2. El Niño Amplification

The 2023–2024 El Niño event played a major role in elevating sea surface temperatures across the tropical Pacific. El Niño reduces upwelling of cooler waters and alters wind patterns, allowing warm surface layers to expand and persist. This event intensified global SST anomalies and contributed to widespread marine heatwaves.

3. Reduced Ocean Mixing

Warmer surface waters increase stratification—meaning the ocean layers mix less. This traps heat in the upper ocean and prevents cooler, deeper waters from rising. As a result, surface temperatures stay elevated longer, and marine ecosystems experience prolonged thermal stress.

4. Changes in Aerosols and Cloud Cover

Some regions experienced reduced aerosol concentrations and altered cloud regimes, which allowed more solar radiation to reach the ocean surface. This effect, though secondary, contributed to localized warming and reduced the ocean’s ability to cool through radiative processes.

5. Feedback Loops

Once surface temperatures rise, they can trigger feedbacks that reinforce warming. For example, warmer waters reduce wind-driven mixing and increase evaporation, which adds moisture to the atmosphere and can intensify storms. These feedbacks make marine heatwaves more persistent and harder to predict.

Together, these mechanisms explain why the ocean heat surge of 2024–2025 was so extreme—and why Costa Rica’s coastal ecosystems are feeling the impact. In the next section, we’ll zoom in on how these global patterns are playing out locally.

Section 4: Costa Rica’s Coastal Realities

While global ocean warming sets the stage, its impacts are felt most acutely at the local level. Costa Rica’s Pacific and Caribbean coasts are both vulnerable to marine heatwaves, but they respond differently due to distinct oceanographic conditions, seasonal cycles, and ecological communities.

Pacific Coast (Eastern Tropical Pacific)

- Hotspots: The Gulf of Papagayo, Nicoya Peninsula, and areas near Isla del Coco have experienced elevated SSTs, especially during El Niño phases.

- Seasonal anomalies: During the dry season (December–April), reduced cloud cover and weaker upwelling amplify surface warming. In 2024, SSTs in Papagayo exceeded climatological norms by +2°C for several weeks.

- Ecological stress: Coral reefs in this region, particularly those dominated by Pocillopora and Porites, showed signs of bleaching and reduced reproductive success. Pelagic species such as manta rays and whale sharks may shift their migratory patterns in response to thermal changes.

Caribbean Coast

- Persistent warming: The southern Caribbean, including Cahuita and Gandoca-Manzanillo, saw prolonged marine heatwaves in 2024, with SST anomalies exceeding +1.5°C for over 30 days.

- Coral vulnerability: Shallow reefs dominated by Acropora palmata and A. cervicornis are highly sensitive to thermal stress. Bleaching events were reported by local dive operators and conservation groups.

- Visibility and tourism: Warmer waters reduce water clarity and increase algal growth, affecting snorkeling and diving experiences. These changes have direct implications for eco-tourism and local livelihoods.

Isla del Coco

- Remote but not immune: Despite its isolation, Isla del Coco experienced elevated SSTs and reduced nutrient upwelling, which may affect plankton dynamics and predator-prey relationships.

- Monitoring importance: As a biodiversity hotspot, Coco serves as a sentinel site for tracking long-term ocean changes in the Eastern Tropical Pacific.

Local Timeline: 2024–2025

- Early 2024: Strong El Niño conditions drive SST anomalies in the Pacific; first signs of coral stress appear.

- Mid 2024: Caribbean heatwaves intensify; NOAA Coral Reef Watch issues Level 2 bleaching alerts.

- Late 2024: SSTs remain high despite El Niño weakening; subsurface heat persists.

- 2025 outlook: Transition to La Niña may cool surface waters, but accumulated heat and stratification could sustain regional stress.

Costa Rica’s coastal ecosystems are already responding to these changes. In the next section, we’ll explore how emblematic species—from corals to sea turtles—are being affected.

Emblematic Species and Ecosystem Impacts

Costa Rica’s marine biodiversity is rich and fragile. As ocean temperatures rise, key species and habitats face mounting stress. The effects vary by region and species, but the common thread is disruption—of life cycles, habitat conditions, and ecological balance.

Coral Reefs

- Bleaching events: Elevated SSTs trigger coral bleaching, where corals expel their symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae), losing color and vital energy sources. In 2024, reefs in both Pacific and Caribbean zones showed signs of bleaching, with NOAA Coral Reef Watch issuing Level 2 alerts.

- Species affected:

- Pacific: Pocillopora, Porites, and Montipora species.

- Caribbean: Acropora palmata, A. cervicornis, and Diploria species.

- Recovery challenges: Repeated heatwaves reduce recovery time, increase disease susceptibility, and lower reproductive success.

Sea Turtles

- Nesting impacts: Sand temperature influences hatchling sex ratios. Warmer sands skew populations toward females, potentially destabilizing future generations.

- Feeding grounds: Heat stress affects seagrass beds and jellyfish populations, altering food availability for green and leatherback turtles.

Marine Mammals

- Migration shifts: Species like humpback whales and spinner dolphins may alter migratory routes or timing due to changes in prey distribution and water temperature.

- Acoustic environment: Warmer waters can affect sound propagation, potentially disrupting communication and navigation.

Mangroves and Seagrasses

Resilience and risk: These habitats offer some thermal buffering but are vulnerable to prolonged heat and low oxygen conditions.

Carbon storage: Heat stress may reduce their ability to sequester carbon, weakening their role in climate mitigation.

Human Impacts and Management Responses

The warming of Costa Rica’s coastal waters is not just an ecological issue—it’s a human one. Communities that depend on healthy marine ecosystems for food, income, and cultural identity are already feeling the effects. As marine heatwaves intensify, proactive management and community engagement become essential.

Fisheries and Livelihoods

- Species displacement: Warmer waters can push fish populations away from traditional fishing zones, reducing catch reliability and increasing fuel costs for small-scale fishers.

- Reproductive cycles: Changes in temperature affect spawning seasons and larval survival, disrupting the timing and abundance of key species like snapper, grouper, and tuna.

- Economic vulnerability: Coastal communities reliant on artisanal fisheries face income instability and may require support through adaptive policies and diversification.

Tourism and Recreation

- Coral reef degradation: Bleached reefs lose their visual appeal and biodiversity, affecting snorkeling and diving experiences—key attractions in areas like Cahuita, Golfo Dulce, and Isla del Coco.

- Visibility and safety: Algal blooms and reduced water clarity can impact tour operations and visitor satisfaction, while warmer waters may increase jellyfish encounters and other hazards.

- Eco-tourism adaptation: Operators are beginning to shift toward low-impact practices, seasonal planning, and educational experiences that highlight conservation.

Coastal Risk and Infrastructure

- Sea level rise: Thermal expansion of seawater contributes to rising sea levels, increasing erosion and flooding risks in low-lying areas such as Puntarenas and Limón.

- Storm intensity: Warmer oceans fuel stronger tropical storms, which can damage infrastructure, disrupt livelihoods, and strain emergency response systems.

Management Priorities

- Thermal monitoring: Expand local SST and coral stress tracking using NOAA Coral Reef Watch and community-based sensors.

- Adaptive closures: Develop protocols for temporary closures of dive sites or fishing zones during peak thermal stress to allow ecosystem recovery.

- Habitat restoration: Support mangrove and coral restoration projects that enhance resilience and carbon storage.

- Education and outreach: Engage schools, guides, and travelers in understanding marine heat impacts and promoting responsible behavior.

Costa Rica’s strength lies in its commitment to conservation and community-based stewardship. By aligning science with local action, the country can lead in adapting to ocean warming while protecting its marine heritage.

Visualizations and Interactive Storytelling

To make ocean warming tangible for a broader audience, visual tools and interactive elements are essential. They help translate complex data into intuitive experiences, allowing readers to explore patterns, timelines, and species impacts in a way that feels personal and immersive.

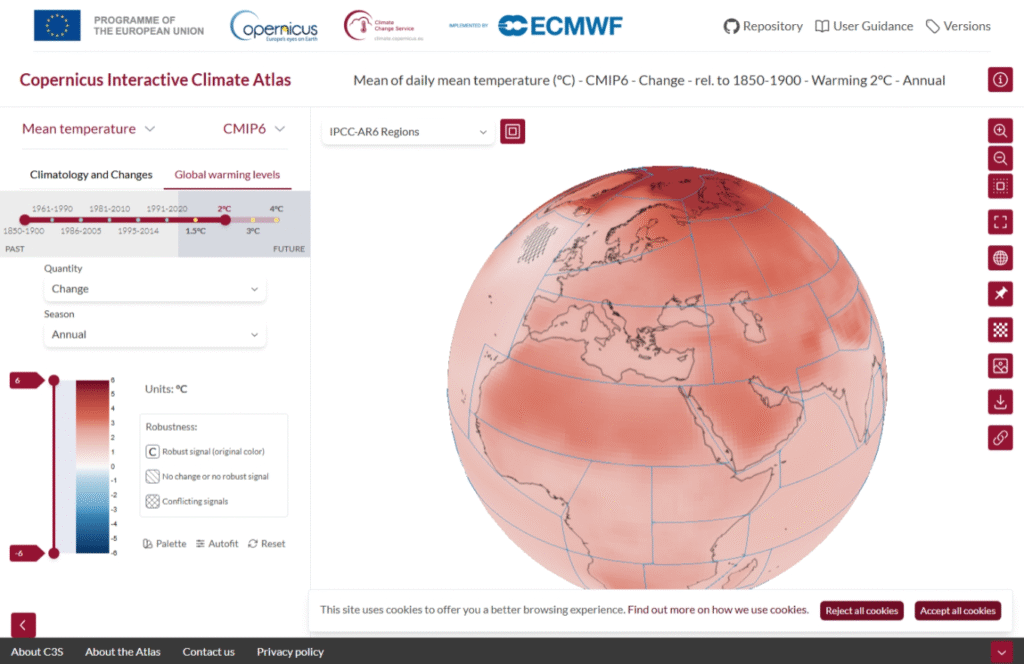

Dynamic SST Maps

- Weekly anomalies: Use NOAA OISST data to generate animated maps showing sea surface temperature anomalies across Costa Rica’s Pacific and Caribbean coasts.

- Hotspot markers: Highlight key regions like Golfo de Papagayo, Cahuita, and Isla del Coco with pop-ups showing temperature deviations and ecological notes.

Reef Thermographs

- DHW timelines: Display Degree Heating Weeks (DHW) for selected reef sites to show cumulative thermal stress over time.

- Bleaching alerts: Integrate NOAA Coral Reef Watch alert levels to visualize when and where bleaching risk peaked.

Species Impact Cards

- Interactive profiles: Create clickable cards for emblematic species (e.g., Acropora palmata, green sea turtle, humpback whale) showing how warming affects their behavior, habitat, and reproduction.

- Seasonal overlays: Link species life cycles to SST timelines to show mismatches or vulnerabilities.

Ocean “Breath” Animation

- Stratification vs. mixing: A short animation showing how warm surface layers reduce vertical mixing, trapping heat and nutrients.

- Narrative metaphor: Frame the animation as the ocean’s disrupted breathing—an emotional cue that connects viewers to the urgency of change.

Visitor Engagement Tools

- Heatwave tracker: Allow users to explore past and current marine heatwaves by region and severity.

- Citizen science portal: Invite divers, guides, and travelers to report coral bleaching, unusual species sightings, or water clarity changes.

These visual elements not only enhance understanding—they invite participation. By turning data into stories, Costa Rica Species can empower its audience to see, feel, and act on the changes unfolding beneath the surface.

Section 8: Methodology and Definitions

To ensure clarity and scientific accuracy, this article draws from peer-reviewed sources, global climate monitoring systems, and standardized definitions used in oceanography and marine ecology. Below is an overview of how data were selected, processed, and interpreted.

Data Sources

- Sea Surface Temperature (SST):

- Derived from NOAA’s Optimum Interpolation SST (OISST) dataset, which combines satellite and in-situ measurements.

- Anomalies calculated against the 1991–2020 climatological baseline.

- Ocean Heat Content (OHC):

- Based on annual assessments published in Advances in Atmospheric Sciences by Cheng et al., covering 0–2000 m depth.

- Provides insight into subsurface warming and long-term energy accumulation.

- Marine Heatwaves (MHW):

- Identified using the definition by Hobday et al. (2016): periods when SST exceeds the 90th percentile of local climatology for ≥5 consecutive days.

- Severity classified as Moderate, Strong, Severe, or Extreme.

- Coral Bleaching Alerts:

- Sourced from NOAA Coral Reef Watch, which uses Degree Heating Weeks (DHW) to estimate thermal stress on coral reefs.

- Level 1 and Level 2 alerts indicate increasing risk of bleaching and mortality.

- ENSO Conditions:

- Monitored via NOAA Climate Prediction Center and Copernicus C3S, tracking El Niño/La Niña phases and their influence on Pacific SST.

Analytical Approach

- Temporal scope: January 2024 to August 2025, with historical comparisons to prior El Niño years (e.g., 1997–98, 2015–16).

- Spatial focus: Costa Rica’s Pacific coast (Nicoya, Papagayo, Isla del Coco) and Caribbean coast (Cahuita, Gandoca-Manzanillo).

- Indicators used: SST anomalies, DHW, MHW duration and intensity, coral bleaching reports, and species distribution changes.

Key Definitions

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| SST | Sea Surface Temperature — the temperature of the ocean’s uppermost layer. |

| OHC | Ocean Heat Content — total thermal energy stored in the ocean, typically measured from surface to 2000 m. |

| MHW | Marine Heatwave — a prolonged period of unusually warm ocean temperatures. |

| DHW | Degree Heating Weeks — cumulative measure of thermal stress on corals over time. |

| ENSO | El Niño–Southern Oscillation — a climate pattern that influences global ocean temperatures and weather. |

This methodology ensures that the article is grounded in reliable data and transparent analysis. In the final section, we’ll explore how readers can take action—whether through conservation, education, or responsible travel.