In meteorology, a cold front is formally defined as the leading edge, or boundary, of an advancing mass of cold air. At the surface, this boundary marks a synoptic-scale transition zone where the colder, denser air mass is actively replacing a warmer, less dense air mass.

While Costa Rica is a tropical nation defined by its proximity to the equator, it is not isolated from large-scale hemispheric weather patterns. The influence of these frontal systems is most pronounced during the boreal winter, typically spanning from November to March. This period aligns with the dry season on the Pacific slope but constitutes a seasonal peak in precipitation for the Caribbean slope, driven largely by these frontal intrusions.

Understanding this recurring atmospheric phenomenon is critical for comprehending its profound impacts on Costa Rica’s rich biodiversity and its societal structures, from agriculture and infrastructure stability to public health.

What is a Cold Front? Physical Fundamentals

A cold front represents a dynamic, three-dimensional interface separating two distinct air masses. These masses exhibit significant gradients (differences) in key physical properties: temperature, humidity (dew point), and density.

The fundamental atmospheric dynamics are governed by these density differences. The advancing cold air, originating from polar or high-latitude continental regions, is significantly denser (and often drier) than the incumbent warm, moist tropical air.

This density differential forces the cold air to act as a wedge, burrowing underneath the warmer, more buoyant air mass. This process, known as dynamic or frontal lifting, forces the warm air to ascend rapidly.

Immediate Consequences

As the warm, often moist, air is forced violently upward, it cools adiabatically (by expansion as pressure decreases with altitude). This cooling forces the air parcel to reach its saturation point, leading to condensation of water vapor.

The immediate results are the formation of vertically developed clouds—such as Cumulonimbus (often associated with sharp, intense precipitation) or extensive Nimbostratus layers (associated with steady, widespread rain)—and the onset of precipitation.

Observation and Representation

On synoptic weather maps, cold fronts are conventionally depicted as a blue line marked with solid triangles (barbs) that point in the direction of the front’s movement.

Getty Images

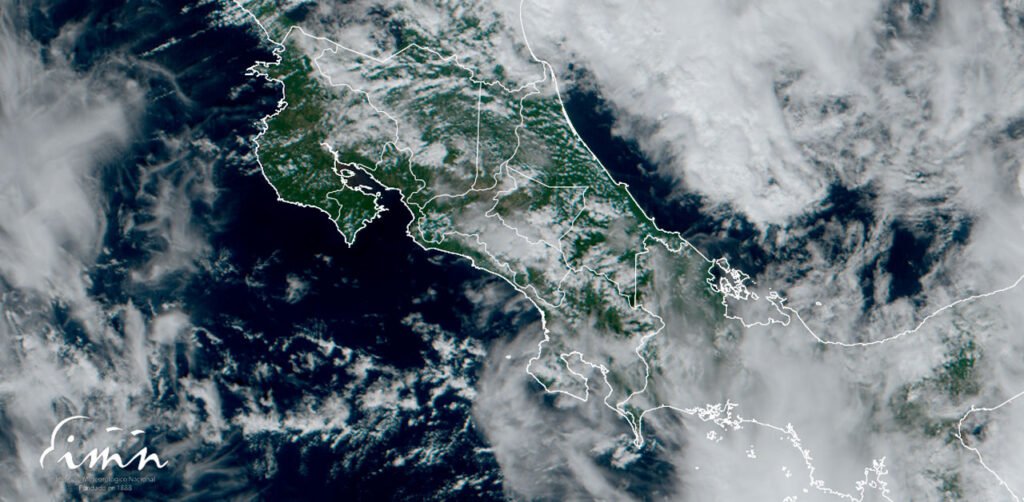

Via satellite remote sensing (specifically in water vapor or infrared imagery), these fronts are identifiable by the distinct, organized bands of clouds aligned with this lifting mechanism.

Formation and Routes of Cold Fronts

The genesis of the cold fronts that impact Costa Rica lies far to the north, originating primarily as polar or Arctic continental air masses over the high-latitude regions of North America, particularly during the boreal winter.

These frigid, dense air masses are set in motion by large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns. Their southward advance is typically driven by robust migratory anticyclones (high-pressure systems) that form in the wake of mid-latitude cyclones. The clockwise circulation around these high-pressure centers actively advects (transports) the cold air equatorward.

The predominant trajectory follows a north-to-south path across the United States, crossing the Gulf of Mexico before arriving in Central America.

Topographic Amplification and Channeling

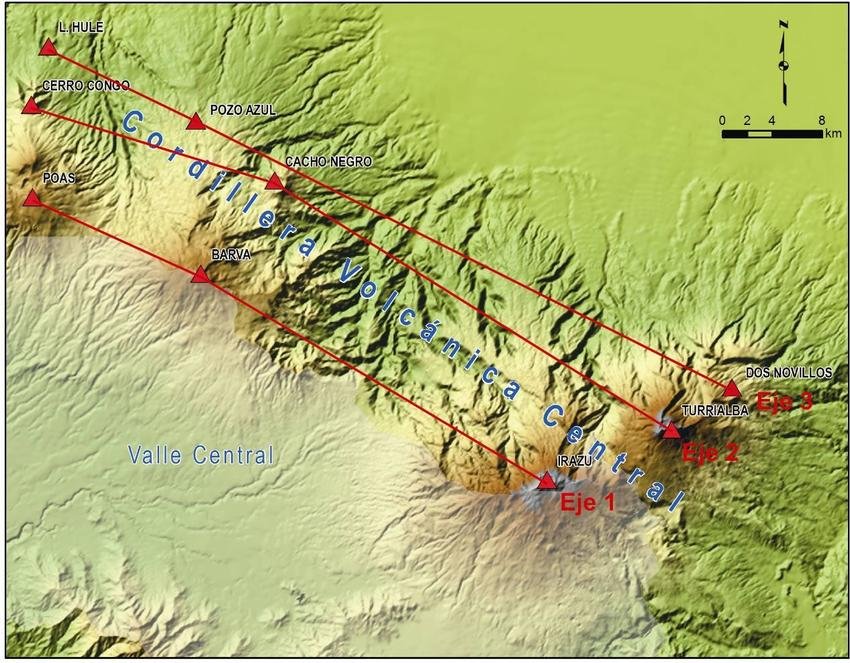

While the front itself is a large-scale feature, its localized effects in Costa Rica are profoundly modified by the country’s complex orography. The high central mountain ranges (Cordilleras) act as a natural barrier.

- Caribbean Slope: The northeasterly winds associated with the front collide directly with the Caribbean slopes, forcing strong orographic lift. This mechanism dramatically amplifies cloud formation and results in persistent, often heavy, precipitation.

- Central Valley & Pacific: The air mass is “channeled” through lower mountain passes and valleys (such as the Central Valley). This funneling effect causes a significant acceleration of the wind, leading to the strong, gusty “Nortes” (northerly winds) characteristic of these events.

Influence of Climate Change

The relationship between climate change and cold front frequency or intensity is complex. Current research investigates competing hypotheses:

- Reduced Frequency: “Arctic Amplification” (the Arctic warming faster than the tropics) may reduce the overall north-south temperature gradient, potentially decreasing the frequency of strong polar outbreaks.

- Increased Intensity: A warmer atmosphere, in general, has a higher water vapor capacity. This suggests that when frontal precipitation events do occur, they may yield higher rainfall totals.

Local Climatic Effects

The arrival of a cold front (known locally as frente frío or empuje frío) triggers a distinct and abrupt set of changes in Costa Rica’s local weather conditions.

Temperature Decrease

The most widely perceived effect is a sensible drop in ambient temperature. While Costa Rica’s tropical location prevents genuinely “cold” (i.e., freezing) conditions outside of high mountain peaks, the decrease is significant relative to the tropical norm.

- Typical Figures: In the populous Central Valley (approx. 800-1,500m elevation), temperatures can drop by 5°C to 10°C from their seasonal average. In higher elevation areas like the Cerro de la Muerte, temperatures can approach or dip below 0°C.

- Interannual Variability: The magnitude of these temperature drops varies significantly from year to year, depending on the specific properties (origin, moisture content) of the polar air mass.

Wind Pattern Modifications

The passage of the front is almost always associated with a dramatic intensification of the northeasterly trade winds (los Alisios).

- Pattern Shift: The winds become strong, persistent, and often turbulent, locally referred to as “Nortes.”

- Observed Intensities: Sustained wind speeds of 40-60 km/h with gusts exceeding 80-100 km/h are common, particularly in the northern Pacific (Guanacaste), the Central Valley, and especially in mountain passes where a “funnel effect” (venturi effect) occurs.

Precipitation Anomalies

The impact on rainfall is starkly divided by the central mountain ranges:

- Caribbean & Northern Zone: These regions bear the brunt of the front’s moisture. The strong Alisios, laden with moisture from the Caribbean Sea, are forced upward by the topography (orographic lift), resulting in persistent, often heavy, widespread rainfall and saturated conditions that can last for several days.

- Pacific Slope: In contrast, the Pacific slope (Central and South) experiences a “rain shadow” effect, leading to drier, sunnier, and clearer skies. However, the intensity of the winds can often force moisture over the continental divide, causing light, drizzly rain and persistent fog (neblina) on the Pacific-facing slopes of the mountains, including parts of the Central Valley.

Changes in Wind Chill Factor (Sensación Térmica)

The combination of lower temperatures and high-velocity winds creates a “wind chill” effect. This sensación térmica (perceived temperature) often feels significantly colder to the populace than the measured air temperature would suggest, as the wind accelerates the rate of heat loss from the body. This is often the most significant impact on human comfort.

Ecological Impact and Biodiversity

Cold fronts function as a significant, periodic climatic pulse or disturbance, exerting profound selective pressure and driving ecological processes across Costa Rica’s diverse ecosystems.

Consequences by Ecosystem

- Montane Ecosystems (e.g., Cloud Forests): These high-elevation zones experience the most direct temperature drops. This can induce physiological stress in flora and fauna adapted to stable, cool conditions. The persistent wind and neblina (fog) also alter the light availability and moisture regime, impacting epiphytic communities (orchids, bromeliads) that depend on atmospheric moisture.

- Tropical Rainforests (e.g., Caribbean lowlands): The primary impact here is mechanical and hydrological. Strong wind gusts can cause tree falls (windthrow), opening gaps in the canopy. These gaps alter light and temperature conditions at the forest floor, triggering new successional cycles. Intense, prolonged rainfall leads to soil saturation and can trigger landslides.

- Coastal Zones: Strong winds generate high-energy wave action and coastal erosion, particularly on the Caribbean coast. In the northern Pacific (e.g., Gulf of Papagayo), the nutrient-poor waters can be temporarily enriched by coastal upwelling induced by the strong offshore winds, briefly boosting marine productivity.

Effects on Species Phenology and Behavior

The abrupt environmental shift acts as a critical cue for many species:

- Phenology: The drop in temperature and change in water availability can trigger mass flowering or frucification (fruiting) events in certain plant species. Conversely, it can damage sensitive new growth or flowers in others (e.g., coffee).

- Migration and Movement: These events are crucial for avian migration. Many neotropical migratory birds use these strong northerly tailwinds to facilitate their southward journey. Resident fauna, such as insects, amphibians, and reptiles, may seek shelter (e.g., in burrows, under leaf litter) and enter periods of reduced activity or torpor to conserve energy.

- Food Availability: The high winds can strip trees of fruit and leaves, leading to a temporary scarcity of food for frugivores and herbivores, but a simultaneous boon for ground-feeding insectivores.

- Physiological Adaptation: The phenomenon of deciduousness (seasonal leaf-shedding) in the dry tropical forests of the Pacific (e..g., Guanacaste) is strongly linked to these events. The arrival of the dry, windy Alisios signals the end of the wet season, triggering leaf drop as a water-conservation strategy.

Implications for Human Activity and Health

The impacts of cold fronts extend beyond the natural environment, directly influencing human economic activity, infrastructure stability, and public health.

Agricultural Activity

These events pose a significant threat to agricultural production, primarily through mechanical and thermal stress:

- Crop Damage: Strong winds can cause the “lodging” (bending or breaking) of tall-stalk crops like bananas and corn. They also cause desiccation (windburn) and physical damage to high-value horticultural crops and fruits.

- Protection of Sensitive Crops: In highland areas, the sharp temperature drop can damage sensitive crops like coffee, particularly if it coincides with the delicate flowering stage. Farmers must implement protective measures, such as windbreaks or temporary row covers.

Infrastructure Risks and Prevention

The high-velocity winds associated with empujes fríos exert significant mechanical stress (wind loading) on man-made structures:

- Power Grid: The national electrical grid (tendido eléctrico) is highly vulnerable. The primary risks are twofold: 1) falling trees and large branches (often saturated with rain) onto power lines, and 2) the direct failure of poles or transformers due to wind stress. Widespread power outages are a common result.

- Structures: Lightweight roofing materials, particularly metal lamina, are susceptible to being uplifted or torn off by turbulent gusts, requiring preventive maintenance and adherence to building codes.

Public Health

There is a documented correlation between the arrival of cold fronts and an increase in specific public health issues:

- Respiratory Illnesses: The cold, dry air can irritate the human respiratory mucosa, lowering resistance to viral agents. This often leads to seasonal peaks in influenza, the common cold, and other respiratory infections.

- Allergies and Asthma: The strong winds aerosolize and transport high concentrations of particulate matter, including pollen, dust, and mold spores. This spike in airborne allergens can trigger severe episodes of allergic rhinitis and asthma in susceptible populations.

Benefits for Ecotourism

Conversely, on the Pacific slope, these events often create optimal conditions for tourism:

- Improved Visibility: The frontal system effectively “scours” the atmosphere of aerosols, particulates, and haze, resulting in exceptionally clear, “crystalline” skies. This provides outstanding atmospheric visibility for volcano viewing, photography, and coastal vistas.

- Comfort: The associated decrease in temperature and humidity makes strenuous activities, such as hiking in national parks, significantly more comfortable for visitors.

Monitoring and Prediction in Costa Rica

Accurate forecasting and monitoring of cold fronts are critical for national preparedness, allowing sectors from agriculture to emergency management to mitigate potential risks.

MTC: The Role of the National Meteorological Institute (IMN)

The Instituto Meteorológico Nacional (IMN) is Costa Rica’s official agency responsible for atmospheric monitoring and forecasting.

- Early Warning Systems: The IMN issues public advisories (Avisos Meteorológicos) and warnings (Alertas) as a cold front approaches. These bulletins detail the expected timing, intensity (particularly of wind and rain), and geographic areas likely to be most affected. This information is disseminated to the public and, crucially, to the National Emergency Commission (CNE) to activate regional response plans.

MTC: Technology in Use

A multi-layered technological approach is employed to track these large-scale systems and model their local impacts:

- Geostationary Satellites (GOES): These are the primary tools for identifying and tracking the formation and advance of polar air masses and their associated cloud bands long before they reach Central America.

- Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) Models: The IMN runs and analyzes global and regional computer models (like GFS, ECMWF) to predict the front’s trajectory, timing, and the likely severity of its associated wind and precipitation.

- Surface Weather Stations: A national network of automated weather stations (estaciones meteorológicas) provides real-time, ground-truth data on temperature drops, wind speed/direction, and rainfall accumulation as the event unfolds.

- Weather Radar: Radar systems are essential for monitoring the mesoscale (local) development of precipitation, allowing for short-term warnings (nowcasting) of intense rain bands and potential flash flooding, especially on the Caribbean slope.

MTC: The Importance of Citizen Monitoring

In recent years, “citizen science” and public reports have become a valuable supplement to official data.

- Community Reports: Social media and dedicated platforms allow citizens to report real-time conditions (e.g., fallen trees, local flooding, extreme wind gusts).

- Crowdsourced Data: Data from private, high-density weather station networks (like Weather Underground) and mobile applications help fill observational gaps, especially in complex terrain, providing a more granular view of the front’s impact.

Practical and Conservation Recommendations

Given the recurring and predictable nature of cold fronts, proactive measures can significantly mitigate their negative impacts on both human populations and vulnerable wildlife.

MTC: Public Guidance

For the general population, preparedness focuses on safety and resource protection:

- Attire and Health: Residents, particularly in the Central Valley and highlands, are advised to wear layered, warm clothing. Special attention should be given to vulnerable populations (elderly and children) to prevent hypothermia or respiratory distress.

- Home and Vehicle Protection: Secure roofing materials, trim tree branches that overhang homes or power lines, and secure outdoor objects (e.g., furniture, signage) that could become projectiles. Postpone non-essential travel, especially in mountainous areas prone to landslides or high winds.

- Activity Planning: Outdoor recreational activities, especially boating (due to high seas) and hiking (due to wind, fog, and falling branches), should be postponed during the peak of a strong event.

MTC: Minimizing Wildlife Impact

Conservation efforts should focus on reducing ancillary stress on fauna and flora during these events:

- Habitat Integrity: Maintaining healthy, intact forest corridors allows animals to move to more sheltered microclimates. Preserving robust ground cover (leaf litter, logs) provides critical refuge for amphibians, reptiles, and invertebrates.

- Supplemental Resources: In areas with high concentrations of nectar-feeding birds (like hummingbirds) that are affected by flower loss, supplemental feeders can provide a temporary, critical energy source.

- Fire Prevention: In the dry Pacific regions, the combination of strong Alisios and dry biomass creates extreme fire hazard conditions. Strict fire prevention protocols are essential during this period.

MTC: Environmental Education

Promoting public understanding is key to long-term adaptation. It is vital to communicate that while these events pose risks, they are a fundamental part of the natural climatic cycle in Costa Rica. They are not anomalies but rather a necessary “reset” that drives ecological processes like forest succession, migration, and plant reproduction.

Projection and Future Trends

Predicting how anthropogenic climate change will specifically alter the dynamics of cold fronts in Central America remains a significant scientific challenge. Current climate models present complex and sometimes competing signals regarding their future frequency and intensity.

MTC: Climate Model Projections

The scientific community is investigating two primary, opposing hypotheses:

- Hypothesis 1: Decreased Frequency/Intensity. This argument is based on Arctic Amplification—the phenomenon where the Arctic is warming at a rate more than double the global average. This rapid warming reduces the overall thermal gradient (temperature difference) between the polar regions and the tropics. A weaker gradient would logically provide less energy to drive strong, deep intrusions of polar air southward, potentially leading to fewer or less intense cold fronts reaching Costa Rica.

- Hypothesis 2: Increased Precipitation Impact. This hypothesis argues that even if fronts become less frequent, a globally warmer atmosphere holds more water vapor (per the Clausius-Clapeyron relationship). When a frontal system does occur, it will traverse a warmer-than-average Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. This allows the air mass to entrain a greater volume of moisture, potentially resulting in more extreme precipitation events and associated flooding on the Caribbean slopes.

MTC: The Need for Interdisciplinary Research

Resolving this uncertainty requires a focused research effort. There is a critical need for high-resolution, regional climate models tailored to Costa Rica’s complex topography.

Furthermore, future research must be interdisciplinary, bridging the gap between climatology and biology. It is no longer sufficient to know if the temperature will drop; we must understand how a change in the timing (phenology) or duration of these events will impact the country’s biodiversity. Investigating this climate-biodiversity nexus is essential for predicting species vulnerability and developing robust conservation and agricultural adaptation strategies.

Cold fronts are a definitive and recurring feature of Costa Rica’s annual climatic cycle, demonstrating that even a tropical nation is deeply interconnected with large-scale hemispheric weather patterns. Far from being mere anomalies, these events function as a critical ecological driver, shaping the country’s biodiversity through periodic pulses of stress and resource modulation.

They are a phenomenon of profound dualism: they bring essential orographic rains to the Caribbean slope while enforcing the seasonal dryness of the Pacific. They also pose significant risks to human infrastructure and agriculture through high-velocity winds, yet simultaneously create ideal conditions for the nation’s vital ecotourism sector.

Understanding the science, origins, and multifaceted impacts of these empujes fríos is essential for accurate weather prediction, effective civil preparedness, and, most importantly, for anticipating the adaptive responses of Costa Rica’s unique ecosystems in the face of a changing global climate.